Every time a fine wine changes hands on the secondary market, it isn’t just the ownership that’s transferred – the wine itself is typically shipped to the new owner, and with each journey comes a risk of spoilage or quality loss. Collectors prize “pristine provenance,” meaning a wine’s history of ideal storage and minimal disturbance. But frequent trading can chip away at that provenance. This article delves into how the chance of spoilage propagates with every trade, compounding over multiple exchanges. We’ll explore the science of what can go wrong in transit, present a defensible mathematical model for risk accumulation up to five trades, and explain why fine wines are particularly vulnerable. Finally, we discuss how savvy collectors mitigate these risks. The hidden cost of each transfer is real. And it’s way higher than many realize.

Every Trade Poses a Risk to Wine Quality

When a bottle is sold on the secondary market, it usually means sending that bottle on a trip. Unlike a winery’s direct shipment (often carefully timed or temperature-controlled), collector-to-collector trades often use standard shipping methods, which exposes wine to a gauntlet of hazards.

“When bottles are shipped and reshipped, that’s where you destroy all the work that we've done in providing years of care in the vineyard and in the cellar” - Pierre Girardin , Winemaker (Burgundy)

Temperature Fluctuations. Wine is highly sensitive to temperature. Extremes of heat or cold can permanently damage it. Heat is the biggest threat, and at elevated temperatures, wines can become “cooked,” developing off-flavors (like stewed or raisiny notes) and chemical imbalances. One industry study monitoring 5,000 wine shipments worldwide found that about 15% of shipments were exposed to extreme heat of 30°C (86°F) in transit. Exposure above 26°C (79°F) for more than 36 hours caused permanent chemical changes in the wine, and at 30°C, permanent damage could occur in as little as 18 hours. In other words, a day and a half in a hot delivery truck can wreak havoc on a fine wine. For routes known to be challenging (for example, shipments from France to Asia in summer), the stats are even worse – nearly half of shipments to China breached 30°C, and on the France-to-China route a staggering 90% hit that level. This illustrates how common and serious heat exposure can be during shipping.

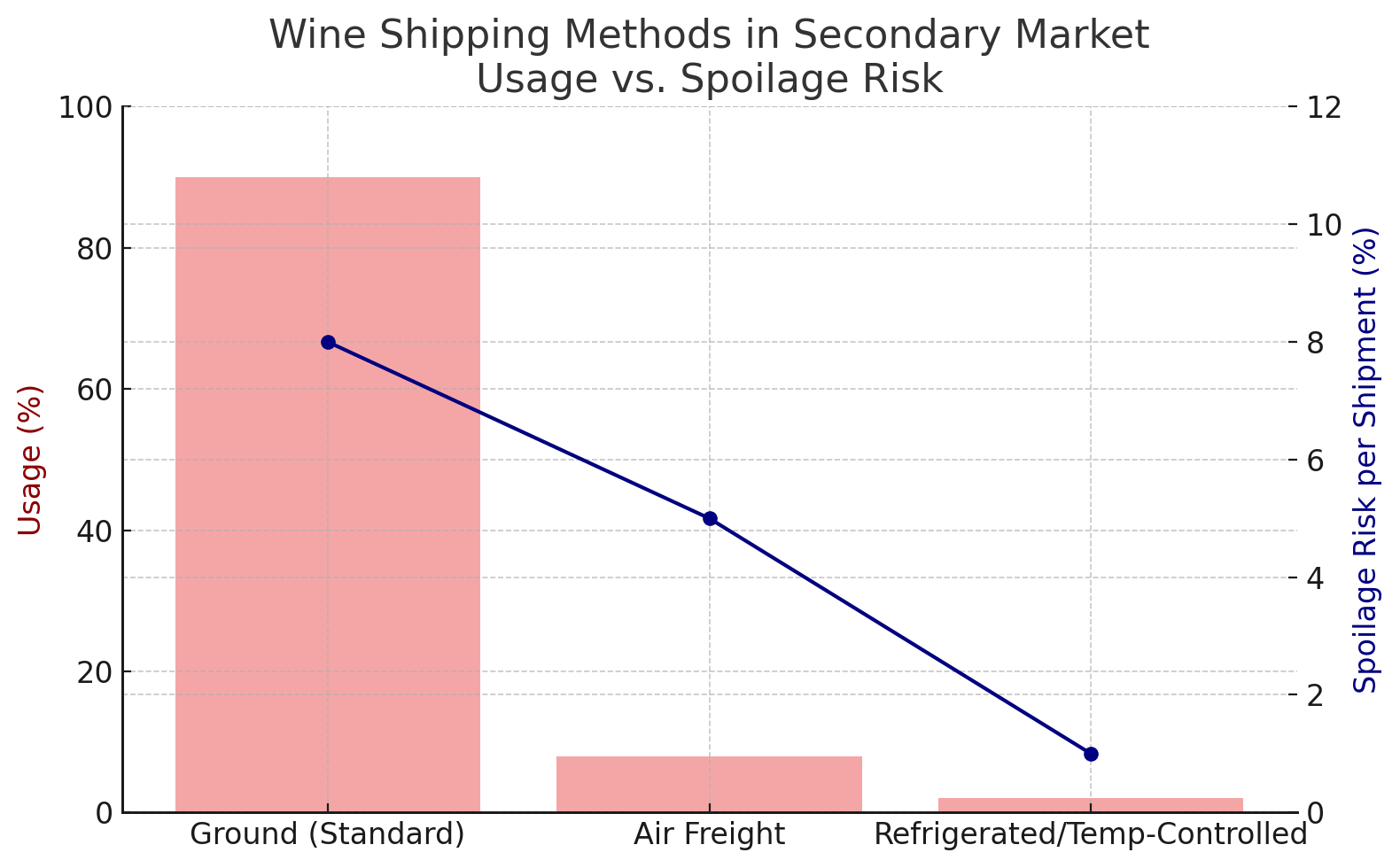

Ground Shipping Realities. In the U.S., about 90% of wine shipments travel by ground. This often means longer transit times and sitting in non-climate-controlled environments (warehouses, truck cargo bays). A few days cross-country in July or a delay on a hot loading dock can easily subject wine to the kind of heat extremes noted above. Even in cooler seasons, ground shipping isn’t temperature-perfect – daytime heat, sunlight on a truck, or overnight freezes can all occur. Wineries often pause shipments in mid-summer for fear of spoilage and leaking corks, but individual collectors selling bottles may not always have the luxury of waiting for ideal weather. Thus, each standard shipment inherently carries some chance of exposing the wine to damaging temperatures.

Vibration and Movement. Unlike a wine resting quietly in a cellar, shipping means motion – trucks jostling, boxes shaking. Vibration can disturb a wine’s sediment (especially in older vintages) and potentially dull its aroma or flavor in the short term. There’s a term “travel shock” used to describe wines showing muted or disjointed taste after travel. While travel shock from vibration is usually temporary (wines often recover after a few weeks of rest), it underscores that transport is not benign. For instance, a controlled experiment by a Master of Wine found no immediate taste difference after shipping, but did note subtle chemical changes – bottles that were air-freighted had lower free SO₂ (an antioxidant preservative) and more browning, indicating slight oxidation. The author suggested that these small impacts from transit, while not always perceptible after one trip, could have a cumulative effect if a wine is shipped multiple times, potentially accelerating its aging.

Pressure Changes. If wines are flown or go over mountains by truck, changes in air pressure can push corks or cause seepage. A cork that jostles out even a millimeter can break the seal, letting oxygen in. Collectors have opened shipped bottles to find the cork protruding and wine leaked into the shipping container – a sure sign of spoilage risk. Freezing is another pressure-related hazard: if wine freezes (around -9°C / 16°F for 12% alcohol wine), it expands and can push the cork out or even crack the bottle. This is less common with standard shipping (since shippers try to avoid extreme cold), but it is possible in winter routes if precautions aren’t taken.

In short, every shipment is a roll of the dice. Even with good packaging and handling, there is some probability that the wine’s quality will be compromised by the journey. Let's take a look at how most wines are shipped: Ground shipping (~90% of shipments) dominates but carries the highest spoilage risk; air freight (~8%) is faster but still introduces vibration and oxidation stresses; refrigerated or temperature-controlled shipping (~2%) is rare but best for preserving quality. This chart tells the story:

Of course, when you trade a bottle once, you accept that chance. But what happens when a bottle is traded multiple times? Those probabilities start to add up.

Compounding Spoilage Risk: The Math of Multiple Trades

Wine collectors often ask: “If my bottle was shipped to me and seemed fine, what’s the harm in trading it again?” The harm is that each new shipment is another exposure to risk – and those risks compound in a probabilistic way. We can model this using well-established principles of probability.

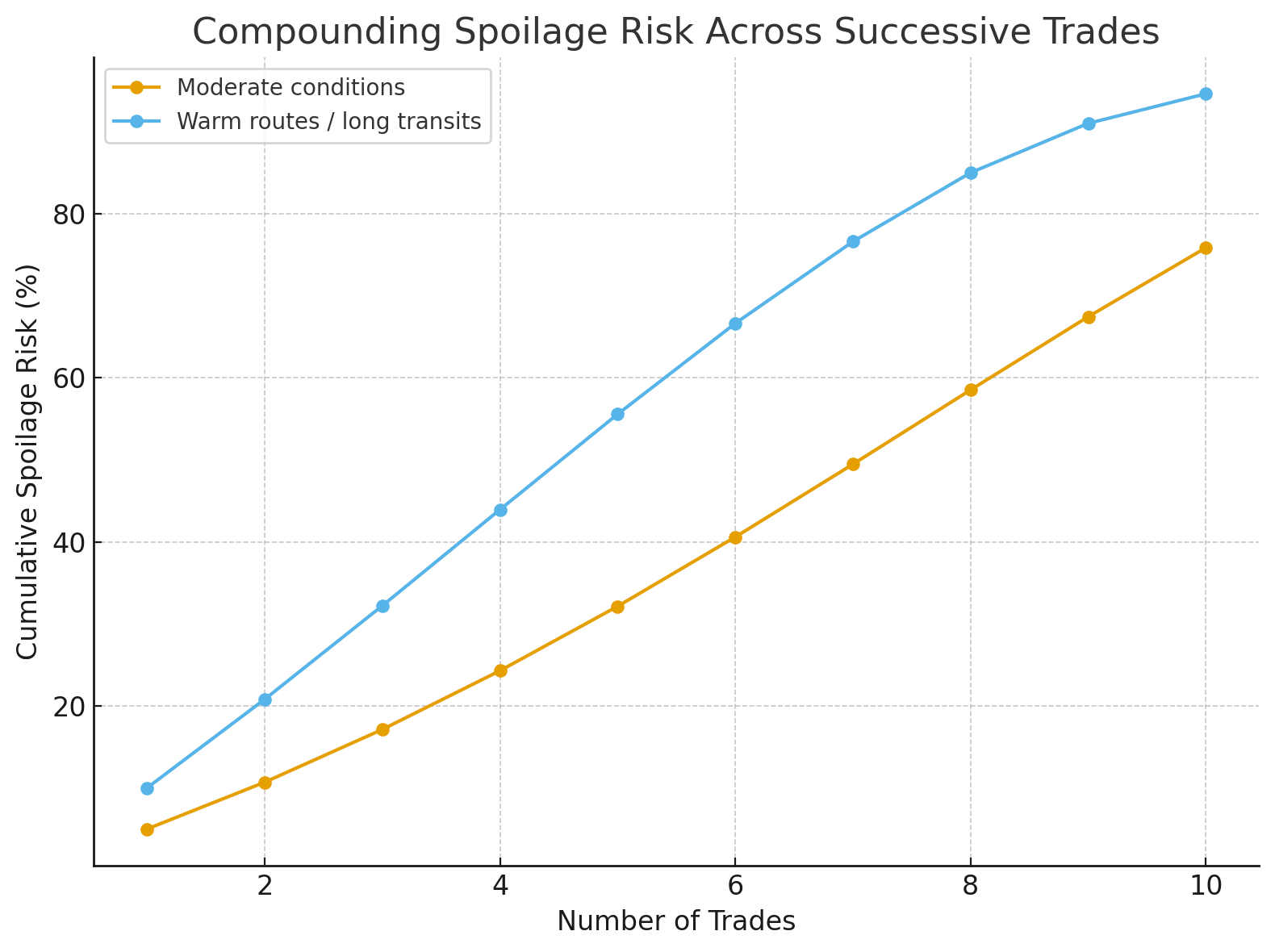

Let’s assume each individual shipment has a probability p of causing spoilage or significant quality loss. This p accounts for all the transit hazards discussed. Perhaps a few percent chance in mild conditions, or higher if shipping in hot weather. Mathematically, the cumulative probability of spoilage after x trades is:

P_total = 1 – ∏(1 – p_n)

Where p_n is the per-trade spoilage risk at trade n. Modeling it in this way accounts for the fact that the chance of survival decreases multiplicatively, not additively, as each new shipment adds risk. To illustrate how this plays out, let's look at two scenarios.

In the first scenario, we'll consider moderate conditions, with a baseline risk ~5% per shipment, growing 20% per trade, capped at 30%. In the second, we'll consider warm routes and longer transits, with baseline risk ~10% per shipment, growing 20% per trade, capped at 40%. These are reasonable assumptions given the data (see references below).

In moderate conditions, a bottle traded five times already faces a 26% chance of being spoiled. On more punishing routes, the cumulative probability exceeds 50% after five trades. Hardly acceptable for anyone who cares about wine.

Fine Wine Has More to Lose with Each Transfer

When bottles are shipped and reshipped, that’s where you destroy all the work that you’ve done,” says Burgundy winemaker Pierre Girardin, reflecting on how years of care in the vineyard and cellar can be undone in transit.

All wines can suffer from poor transit conditions, but wines that are worth keeping for their legacy value or appeal are particularly at risk in secondary-market trading for a few important reasons:

- Older Wines Are Fragile: Rare vintage bottles have spent decades aging to perfection, which makes them delicate. Fluctuations that a young, robust wine might shrug off can permanently harm an older wine’s chemistry. Sediment, fragile corks, and a finely balanced structure mean that even small shocks can cause damage.

- Provenance is Part of the Value: Provenance encompasses who owned the wine and how it was stored. Collectors pay a premium for bottles that have “never moved” from the winery or a single cellar. Each hand-off introduces uncertainty, and a bottle with multiple trades often commands less value.

- Reputation and Buyer Trust: Auction houses emphasize “ex-château” releases for a reason. Multiple trades cast doubt on condition and can even hurt resale appeal. Even minor scuffs to the label or capsule – more likely after repeated shipping – can turn off top buyers.

- Evidence of Cumulative Damage: Scientific evidence suggests repeated shipping degrades wine gradually. The Tofterup MW experiment found cumulative oxidation effects in shipped wines. Another study showed that heat cycles from 0°C to 44°C aged wines an equivalent of 18 months in a short time. Shipping abuse can effectively accelerate a wine’s aging curve.

Bottom line? Fine wines have the most to lose from each transfer. They are both more susceptible to damage and more diminished in market value by a checkered travel history.

Preserving Provenance: How to Mitigate Transfer Risk

If every shipment introduces risk, the most effective strategy for collectors is to minimize movement altogether. The simplest approach is, of course, to buy and hold, or at least sell rarely, ensuring bottles remain undisturbed in one location until the moment they’re opened or finally change hands. When shipping is unavoidable, consolidating multiple bottles into a single shipment is wiser than sending them piecemeal; fewer journeys mean fewer exposures.

Timing and method also matter. Experienced collectors treat the choice of shipping window and service as seriously as an insurance policy. Temperate seasons, refrigerated trucks, or insulated packaging may cost more, but those premiums buy peace of mind. Once a wine arrives, allowing a “rest” period in a stable cellar environment helps it recover from minor transit shock, a practice widely recommended among sommeliers and seasoned buyers.

The gold standard, however, is not to move the wine at all, even when you do sell it. Keeping bottles in their original cellars or bonded professional storage preserves both their physical condition and their provenance record. Collectors increasingly value wines that can be traced back to a single storage facility from the moment of release. In fact, bottles that have “never left bonded storage” now command a premium precisely because their histories are unimpeachable.

Conclusion

The secondary market too often overlooks the compounding nature of spoilage risk. Each trade might seem like a simple ownership transfer, but in reality it’s a new exposure to temperature swings, vibration, and handling errors. The math shows clearly that even under moderate conditions, repeated trades create alarming probabilities of damage – and in hotter routes, five trades can leave a collector with even odds of a spoiled bottle. For fine wine, where provenance is everything, that’s a hidden cost the market can’t afford to ignore.

References

- Soile, Wine in Transit – eProvenance shipping data.

- UPS Capital, Wineries: What’s the True Cost of Not Shipping All Year? (2023).

- John D. Cook Blog, Probability mistake can give a good approximation.

- Vint.co Blog, The Importance of Provenance in Wine Investing.

- Olivia C., How to Safeguard Vintage Wine in Transit.

- Jonas Tofterup MW, Travel shock: Myth or reality? Decanter (2019).

- Butzke, C.E., et al., Influence of Shipping Conditions on Wine Quality, Oeno One Journal.

- Oeno One. “Effects of transport conditions on the stability and sensory quality of wines.”

- Spoilage Risk Compounds (April 29, 2025). Internal synthesis of secondary research and academic studies

- Alston, Julian M., Torey Arvik, Jarrett Hart, and James T. Lapsley. Brettanomics I: The Cost of Brettanomyces in California Wine Production. Journal of Wine Economics, Vol. 16, Issue 1, 2021.

- Wine Spectator. “How Often Did Wine Corks Fail in 2013?”

.svg)